My Taid – Thomas Henry Jones of Tregarth

He’s eight. He likes school and he senses its importance; he likes singing and he senses its power; he likes football because it suspends all senses. He is a good footballer, a first pick, and it is not sense but instinct that guides him on the rough, sloping field where they hurry and scurry and push and clash and feel the thrill of beating the outstretched hand of the keeper.

After school and on Saturdays he leads the horse and cart. Actually, he does not so much lead, as accompany his plodding, blinkered friend on a journey that the old horse could do on its own, save for the fact it has no hands to take the money, or words to remind of the tally. A butcher’s son, with brothers, David and Arthur, he is Thomas Henry, and his eyes and ears register the fear, the trepidation, the worry, the pain and the hard pride, but his innocence can make no sense of the bitter words or the embarrassed apologies when, hand held out, it meets only a promise in the place of cash.

His father is patient. There is no censure when the book is added up, no messenger shot, no raised voice or exasperation. A child’s life is simple until hunger visits, simple until adult struggles bring new tensions, and so, Thomas Henry learns, sings, scores, leads the horse, and watches the sun rise over the Carneddau and set over Ynys Mon. He walks to Moelci to fetch milk. Bald Hill of the Dog… or ‘Milky’ as he translates it in his bilingual experiments. Moel y Ci, Moelci, Milky – where he gets the milk from…

His is as close to a charmed life as there is. Storms brew over Nant Ffrancon, but the hailstones that batter the high peaks are but rain on the rushing wind that scours Tregarth. Storms brew in the quarry, heads are shaken, oaths undertaken and these storms will not blow over. Pennant he is called (Thomas Henry hears the name) will not move. He has taken everything except their will and their tongue, although not for want of trying. The thrill of beating the outstretched hand is not only for the dreaming footballers on the sheep-cropped slopes. There are teachers, strap at the ready, who relish the prospect. The eleventh commandment from the Lord below – mother tongue – thou shalt not survive.

He is ten. Still slight but his legs are strong. He will bequeath those sinewy pins, much later, to one of his own sons, John Merfyn, the professional footballer. The promises, he notices, have become commoner currency. The faces at the doors, he notices, are drawn and serious, and anxiety tinges the apologies. His father goes about business, quietly and thoughtfully (he thinks). The packets of meat get smaller and Thomas Henry is told that there is no need to collect coins for these lean offerings. He rarely goes to the town, but hears his parents and his much older brother speak of strife and fighting and blood and traitors. It goes on like this for months; goes on whilst grim-faced families leave; goes on whilst starvation lurks, and greed pursues its business in full sight. It is the year 1900.

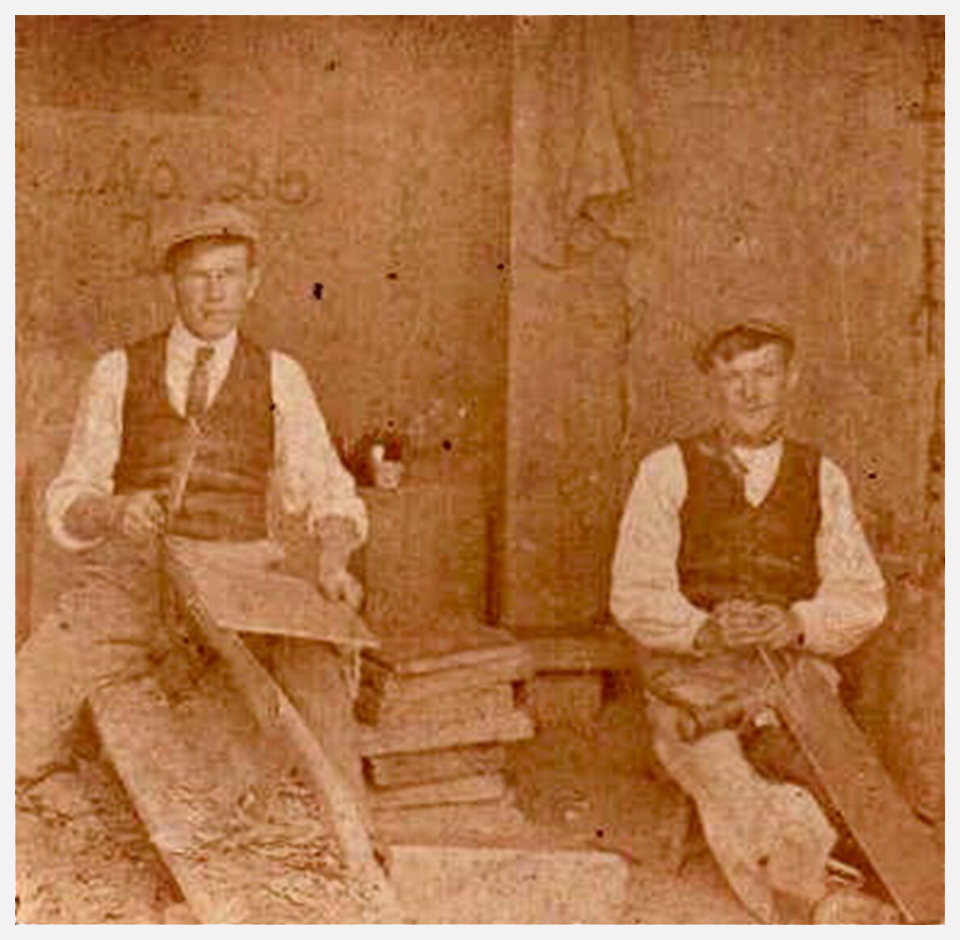

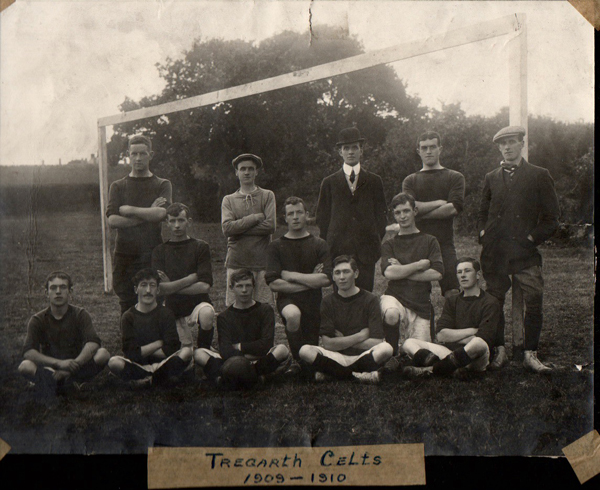

He is sixteen. The butcher’s round is quiet, the quarry is quiet, but he is apprenticed there. The old horse stands in a field. Retired. The ghost-figures of grey-clad families haunt the lanes, and the horse whinnies, mourning their passing to the fields of far-off places they never even dreamed existed, let alone would one day be their home. The strike is long over, no talk for now of traitors – greed’s futile battle with honesty was lost, and the quarry is a shell, but work is work, the choir is good, and like the land, slate runs through him. He is a deft splitter and wins the apprentice cup, his voice resists the dust, and the walk up to the high huts keeps his lungs and legs strong for football. Tregarth Celts are photographed beneath the goal frame, the choir is photographed for a programme – singing and football, hard work and comradeship, family and friends, generosity and tolerance – he did not design these values, he was shown them, he experienced them, he adopted them, he carried them and he passed them on.

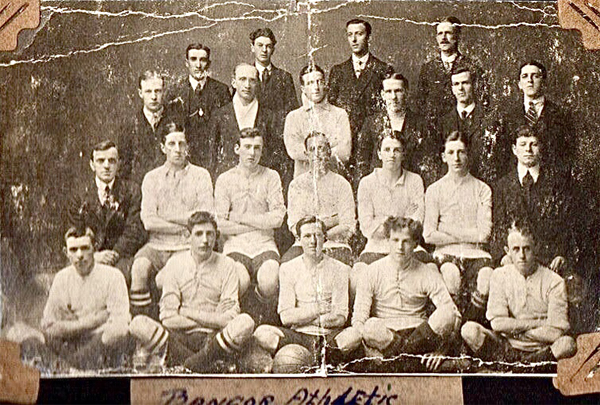

He is twenty-one and Bangor come calling. He leaves the Celts for the City, and they make him captain. Taking the train on match-days, the lads from the quarry clap him on the back, tell him he’s a big-time Charlie now and how that Caernarfon full back wears hobnail football boots. He is genial and takes their affectionate provocation with a smile. He knows (and they know) that whatever the Caernarfon full back wears on his feet, he will not get close to Thomas Henry. Tonight he gets off the train at Felin Hen. One stop early – he fancies to walk the last mile. He passes the church – a constant – not bathed, but rather showered with starlight beneath a giant moon, past the gate, to the house on the lane where Mam waits to hear the score. Dei, sits at the table, Dad is already in bed, Arthur is out courting. Scragged clouds blow across the moon and the first rainspots dab his face as he fetches coal from the lean-to. He looks over the wall, the moonlit skyline that framed his stroll has gone. Yr Elen’s pyramid is lost in the swirl. He adds some logs to the coal in the scuttle, and catches the flicker of the Penmon lighthouse, 90 degrees to the North. A storm. We send slates to shelter them, they send us coal. The fire is stoked. What was the score then? Three-one. To you? To us. Did you score? No. Made two. Panad lad? Aye, thanks David. His Mam says goodnight. The wind rises, latches rattle, leaves skitter. Dei passes him his tea.

He is twenty-six. His sleeves are rolled up and he and his new mates are cleaning equipment at a training camp in Tring, Hertfordshire. It is the furthest he has ever been. They enlisted together, him and Dei. Kitchener pointed at them and they caught the train to Birmingham. There, they went their separate ways. In the camp, he learns quickly. He is used to the spartan conditions and these huts are less draughty than the splitting sheds above Bethesda. Before too long he is at Southampton docks, with a longer journey ahead than the short crossing to France that awaits his brother. In camp, they asked if anyone is familiar with horses and he raised his hand. Could he ride a motorbike? Of course – his uncle Jack from Menai Bridge taught him to ride. The great ship steams past the Isle of Wight – he is heading for Mesopotamia, to the desert, to uncertainty. His brother heads to France, and there survives the trenches for two years until the bullet that rips out his mother’s heart whistles across Sniper’s Alley.

His CO is scared of the horse but parades are part and parcel of discipline, and the show must go on. Consequently, early, before the sun has a chance to sear, he rides out in the half-light over the miles of sand. He looks back at Basra – John Merfyn’s son will see Basra from above years hence – and he pats the horse’s neck. By the time the salutes are raised and the sword-steel glints, the horse will bear its false master through his exhortations, and men from Gwalchmai and Fenny Bentley and Mossley and Llanllechid will stand and sweat, cursing under breath, wondering what will be, whilst king and country wait and the industrial slaughter on the distant Western Front beggars humanity. His days pass, carrying messages to the front by Royal Enfield. He learns that all water must be boiled, that onions are life itself, and that a tribesman in any one-horse village, from the Shatt al-Arab to the Ogwen, is much like the next. Weathered smiles and survival, shelter from the murderous sun or relentless rain, sweet tea, kindness and a handshake are the currency of the poor. When it ends, the regiment are sent to India for convalescence and cholera. Dysentry sees more of them off than any Turkish artillery ever did. He takes news of the death of Prince George to the provincial governor, but the man dismisses him with a quizzical look and returns to his gin and his papers. He steams home, knowing more. For every battered, changed soul he sees bandaged, blind, or imploring a quiet night-time death, he remains the same…

He is 86. He is my Taid. He sits in the chair in Orme Road and smokes rollies watching the news on a black and white television. He walks to the top of Bangor High Street and back, every day, picking up his ‘messages’, smiling and chatting. He hangs a small child upside down by its ankles and smacks its back when he sees it choking in a pushchair. The sweet hits the pavement with a crack. He stands in the dark in our bedroom and tells stories in which the children with nothing have a great time, and Lord Penrhyn is always furious. He tells us about Malan Ddu and Wil Bach and Jacan and he conjures an idyll from a past that was far from easy. He dies in the night, and I know something is wrong because when I get up, Nain is in our kitchen, looking bewildered and hollow.

I’m nearly 58. I miss him. Not because sentimentality has me in a soft grip but because I’d have loved to have been able to walk the Carneddau with him and hear the story of every day of his life. What a book that would have made.